When Nkrumah shouted “Ghana is free forever!” at the Old Polo Grounds, the world believed a new dawn had broken, a united African nation ready to lead the continent into a future of dignity. But inside Ghana, the seeds of conflict that had been quietly planted during the independence struggle were about to germinate.

The opposition’s boycott of the declaration was not the end, it was the beginning of a political storm that would shape the next decade.

A Nation Born Into Suspicion

The absence of the NLM, NPP, and Togoland Congress on independence night cast a long shadow.

They feared the CPP would use its new authority to silence them.

And in the first few months of independence, their suspicions appeared justified.

The Battering Ram Of A Unitary State

Nkrumah’s first major push: absolute central control

The new 1957 constitution gave immense power to the central government. Nkrumah believed a unitary state was the only way to prevent tribal politics, the fastest route to modernisation, and the best tool for nation-building.

But the opposition saw something different. A state where Accra controlled everything. Traditional authorities in Ashanti complained of losing autonomy. Northern leaders feared domination by the south, and Ewe nationalists felt sidelined after the controversial plebiscite.

With every new law, Accra became stronger, and the opposition became more anxious.

CPP Youth Wing: Power On The Streets

To enforce its agenda, the CPP relied heavily on its militant youth groups

The Young Pioneers

The CPP Street Committees

Party “Action Troops” (unofficial but feared)

While Nkrumah promoted them as patriotic forces for national education and civic responsibility, the opposition accused these groups of breaking up opposition rallies, intimidating chiefs, harassing opposition supporters and controlling communities on behalf of the CPP.

In many towns, people whispered that “the CPP had its own police force.”

The Chiefs Under Pressure

One of the most explosive issues was the fate of traditional chiefs. During the independence struggle, Nkrumah promised chiefs that their powers would be respected, they would be partners in national development, and the state would not weaken customary authority

But after independence, new local government reforms and political directives began to erode their influence.

Chiefs accused Nkrumah of betrayal. In Ashanti especially, resentment grew. Many chiefs believed the CPP wanted to break the power of the Asante Kingdom, divide traditional authority, and bring chiefs under party loyalty instead of cultural legitimacy.

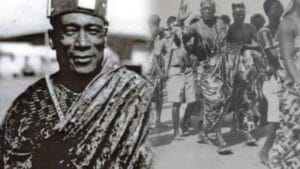

This tension led to the infamous confrontations between CPP operatives and chiefs in Ashanti between 1957–1959.

The Opposition Strikes Back

With tensions rising, the opposition parties began to reorganise.

The NLM strengthened its ties with the Asanteman Council.

The NPP pushed for greater northern autonomy and economic development.

The Togoland Congress continued criticising the 1956 merger.

They began collaborating in Parliament, often blocking CPP initiatives or slowing them down.

This angered Nkrumah, who saw their actions as obstructionist attempts to sabotage national unity.

The Accra Riots And Assassination Attempts

Between 1958 and 1962, there were numerous violent incidents, street clashes between CPP and opposition youth, the Kulungugu bombing attempt on Nkrumah, riots in Accra and Kumasi, and mysterious explosions targeting CPP leaders.

Some incidents were blamed on the opposition; others were possibly orchestrated by rogue groups within the C.P.P. and blamed the opposition for that.

The atmosphere was poisonous.

Nkrumah responded with stronger laws.

The Preventive Detention Act (PDA) — 1958

This single law changed Ghana forever.

It allowed the government to detain anyone without trial for up to five years, renewable indefinitely.

Nkrumah justified it by saying the nation was under threat, and that saboteurs were trying to destabilise the state, and swift action was needed to protect independence.

But the opposition saw it as

“The death of democracy in Ghana.”

Dozens of opposition leaders were arrested.

From Republic To One-Party State

Between 1958–1964, a series of constitutional changes consolidated absolute power.

1960: Ghana becomes a Republic with Nkrumah as Executive President.

1961–62: State enterprises placed under party loyalists.

1964: CPP declared the only legal political party in Ghana.

Parliament became symbolic.

The courts were weakened.

Opposition voices disappeared.

Ghana had become a de facto one-man state.

The Chain Reaction

Every step Nkrumah took, whether out of fear, idealism, or political ambition, deepened the divide.

The same people who boycotted Independence Night became the core of the anti-Nkrumah movement.

This storm finally exploded in 1966, when the military, supported by some opposition elements and foreign actors, overthrew Nkrumah.

His early decisions, some visionary, some authoritarian, some forced by circumstances, and some shaped by political paranoia, created the fractures that haunted the First Republic.

The celebration of 1957 marked unity.

The years after marked division.